As Courtney's post mentioned, I also noticed the contrast between the directness of Blast's allusions to the War with the (if any) illusions I found in Dada magazines. I specifically compared the war issue of Blast with the second issue of the Blind Man, a Dada magazine published in New York in May of 1917. Though the Blind Man is written during the war, it makes virtually no reference to the first World War. Instead, there was a streak of intense American patriotism. Throughout the magazine issue are thoughts on American art, on its potential and growth. Europen art is mentioned in general terms, with French art and some French language scattered within the issue. It seems that instead of mentioning/noticing the war going on in Europe, European art is focused on as a standard to aspire to. On page 10, there is a letter to the Blind Man affirming its work, with the author writing that the support the Blind Man lends to American art will cause people to say "yes, they had an art, back in New York, in the days following the Great War, an art that was a vitalized part of their life..." Essentially, the Blind Man's patriotism, which is reflected through letters from "Midwestern mothers" and American poetry/editorials, is through art rather than through National security.

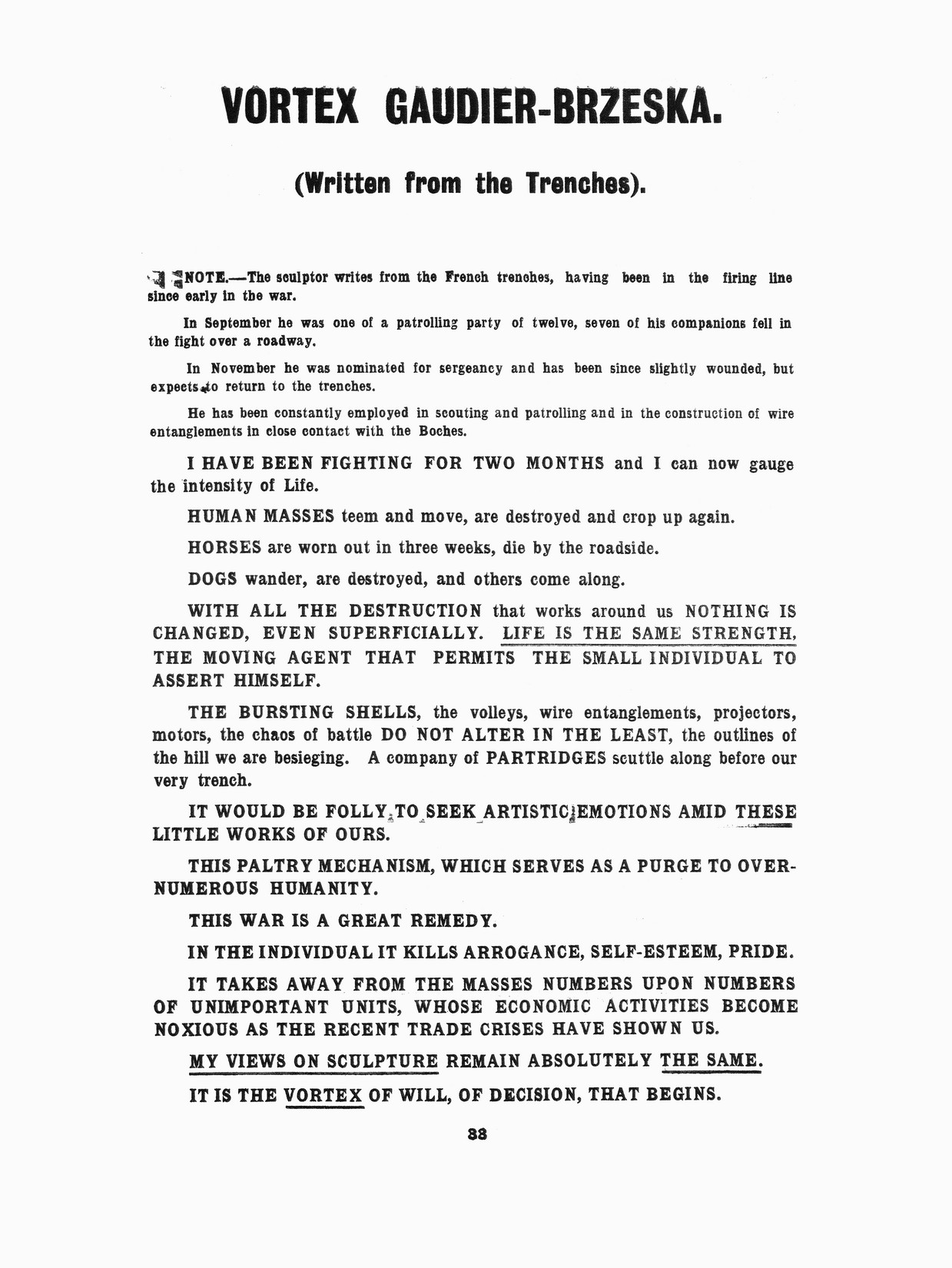

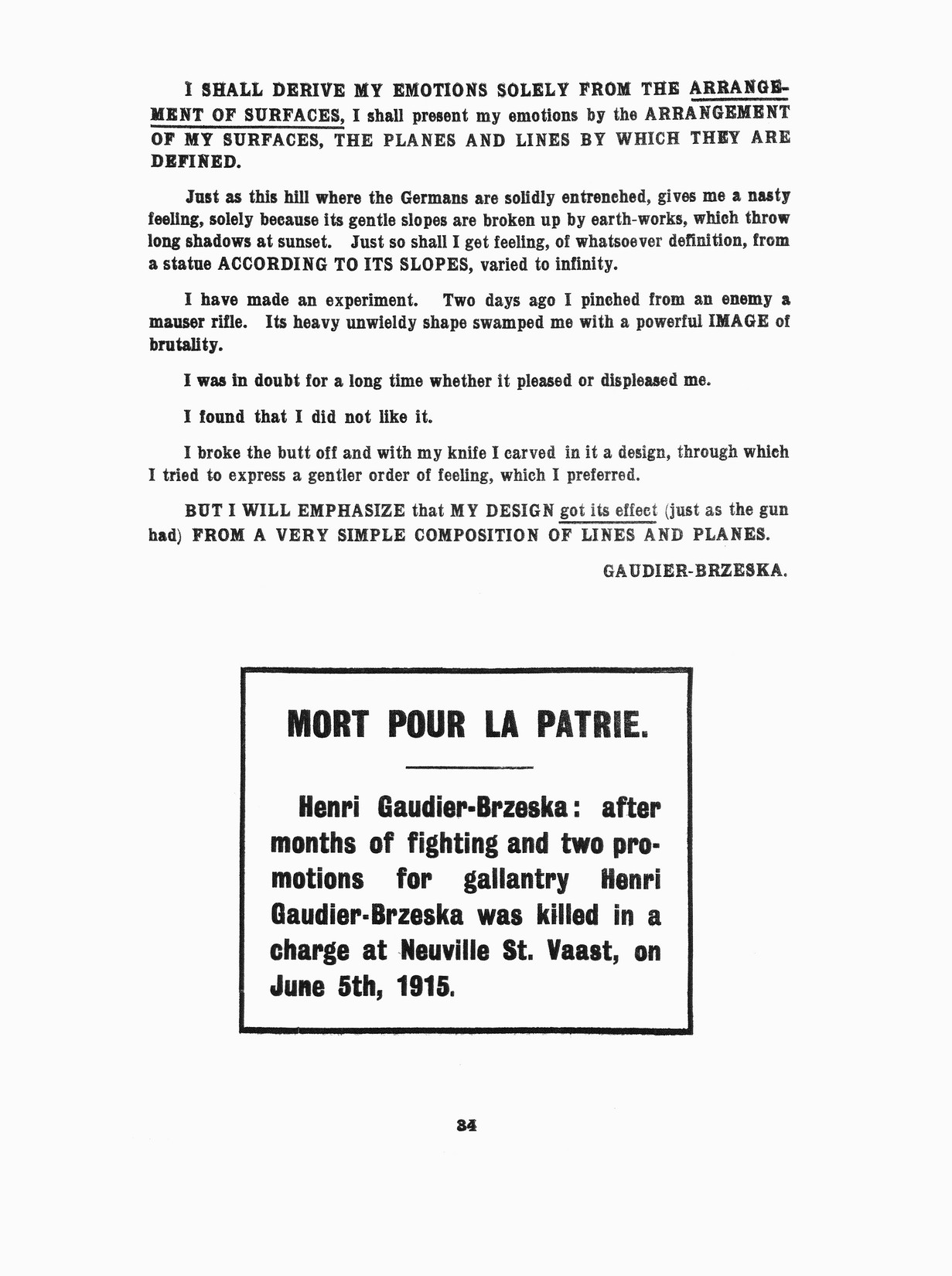

The War issue of Blast, on the other hand, speaks directly about the War. There isn't so much a feeling of patriotism, but there is a rejection of the war. Where the Blind Man perhaps rejects the war by refusing to mention it, Blast speaks directly against it. One piece, Vortex Gaudier-Brzeska (Written from the Trenches), is the perspective of a "sculptor" fighting in the French trenches. He speaks, rants almost, in a piece that seems put into Blast directly to repulse the reader from any feelings of approval about the War. He says that "IT WOULD BE FOLLY TO SEEK ARTISTIC EMOTIONS IN THESE LITTLE WORKS OF OURS" (35). This line, in particular, felt most aligned with the notions of the Dada magazines; that art has no place within a war, or rather that war has no place in art or life. The piece is followed with an abrupt blurb about the author's death within the French trenches, which works only to bring about stronger anti-war sentiments within the reader.