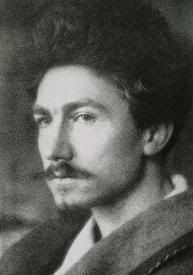

Criticism of Ezra Pound, by Lisa Accardi

Ezra Pound, 1913

Ezra Pound was “everywhere,” according to the Modernist Journal Project. The MJP asserts that Pound contributed literature, editing and criticisms for many small magazines during the Modernist period with a considerable contribution from 1910 into the 1920s during a 12 year stay in London when he shifted his beliefs from Imagism to Vorticism. Pound contributed to the widely distributed The New Age under several names, including William Atheling and B.H. Dias. Pound used the Atheling name to review music in London at the time and the Dias name to review art. Ezra Pound is particularly fascinating because in addition to being a writer, a critic and a “high,” respected Modernist, he was also a teacher. Pound showed readers how to explicate poetry and criticize the arts and literature. Unlike other high modernists, such as James Joyce, author of Ulysses, who was not interested in whether or not readers understood his work, Pound sought to bring art and literature to the masses, yet remained well respected amongst Modernists. Upon my examination of Pound’s work, I noted that many of his writings and criticisms are readable, which further indicates his mission to reach a wide audience. However, that’s not to say that Pound did not write in a pejorative voice, as he seemed aloof and self important, even as he wrote under aliases or wrote in examination of his own career. Notably, this voice was apparent in all of his criticisms, regardless of which alias he was writing under. This consistency makes it fairly easy to recognize his writings. In compiling this report, I sought to examine why Pound contributed to so many small magazines of the time and to criticize some of his contributions to The New Age under all three of his aliases.

Pound published an article in The English Journal in November, 1930 entitled, “Small Magazines.” The article is Pound’s reflection on earlier years and an explanation of the value of small magazines during Modernism. “Small Magazines” is very thorough, if not a bit conceited, and touches upon many of the magazines we discussed in class. This article would be a valuable addition to the syllabus, as it creates historical context in which to read the magazines and gave a clearer picture of the time period. So why did Ezra Pound play such a large role in these magazines? Pound states that, “better magazines failed offensively to maintain intellectual life.” During this time, larger, commercial magazines such as Scribner’s, Harper’s and Conde Nast were in circulation. According to Pound, the way in which articles were chosen for these large magazines was based on how much advertising money the publisher could earn based on the article. If the article had mainstream ideas, advertisers were more likely to peddle their wares in the magazine’s advertising space. Pound refers to the ads in these larger magazines sarcastically by calling them “bright” and “snappy.” If an article contained obscure ideas, it likely wouldn’t garner advertising dollars and would not be published. Pound asserts that this caused a “pervasive monotony” or sameness in magazines, that is to say there was a repetition of ideas in each publication. In contrast, advertising was not a primary concern in small magazines. Therefore, new thoughts and ideas flowed freely in each publication without consideration for monetary gain. Indeed, this is often why small magazines such as Blast or The Blue Review printed so few issues. There was no funding to sustain these magazines. Pound further discusses a public dissatisfaction with larger magazines and his desire to fill that void. Although Pound sought to improve the publishing world, he is displeased with its audience and frustrated at their lack of awareness in the “monotony” of larger publications. He states, “It is also to be observed that people who would not be taken in by a free advertising circular are delighted to pay five cents for a mass of printed paper that costs twenty cents to produce.” Pound is referring to the larger magazine’s epiphany that they could charge below cost for a publication if enough advertising space was sold in each issue. If the magazine was below cost and inexpensive for the consumer, readership would be more widespread. And that’s exactly what these larger magazines – Scribner’s, Harper’s and Conde Nast did, which, according to Pound, perpetuated a cycle of monotony and halted the flow of new ideas into the mainstream.

Pound believed that small magazines such as The Egosist and The Little Review had many positive achievements. One of The Little Review’s goals was to “civilize America and to introduce international standards of criticism.” In his article, Small Magazines, Pound discusses the ways in which The Little Review was indeed successful in its mission as, “An American book is not often as good as a French or European book.” Clearly, his tone is superior and mocking and he makes his distaste for American literature in all its forms evident. Truly, Pound believed it was his responsibility to illuminate the world of important literature, which may be noble if not for the accompanying disparaging snobbery. One can liken it to the teacher who believes there is only one way to learn and if students fail to embrace the method, they are to remain but ignorant fools. Still, Pound felt his efforts triumphant and continued with his mission. “We wanted to set up civilization in America,” he stated. Small magazines were the vehicle to achieve this goal and Pound viewed them as an “honest literary experiment.” He goes on to demonize the larger magazines and one can surmise that he viewed the commercial magazines as uncivilized and primitive when he says that the small magazines are of “infinitely more value to the intellectual life of a nation than exploitation (however glittering) of mental mush and otiose habit.” His elitist attitude and apparent duty to enlighten humanity could only be realized through smaller publications, which is in contrast to his actions because while he was a major contributor to many of the smaller magazines, he also contributed to larger publications such as Scribner’s. Still, Pound is one of the father’s of modernism and is still regaled for his contribution to the time period today.

Additionally, in the spirit of Modernism, Pound did not seek to please his reader. He believed that only in a reader’s discomfort could there be enlightenment and so again mocked larger, commercial magazines. According to Pound, people had the need to feel connected and to discuss topics of common interest, which is why the masses turned to large publications. And in turn, the large publications sought to placate readers, which led Pound to seek out new avenues of print. Pound describes Poetry, a small journal edited by Harriet Monroe as one of the first small magazines to recognize that “verse to be of any intellectual value, could not be selected merely on the basis of immediate earning capacity.” Pound says that this was not a new idea, but Monroe was one of the first editors to put this idea into practice as she chose works to include in her publication. Pound fervently approved and, according to the MJP, he went on to become her foreign correspondent. However, after a while Pound grew weary with Monroe and eventually left the magazine when he realized that she undervalued the intelligence of her readers. Pound implied that Monroe began omitting works that might have great literary significance; if only Monroe put trust in her reader’s intellect. Again, he did not seek to please readers, but it was his duty, however belittling, to instruct and guide them to his interpretation of quality writing. Nonetheless, Poetry is still in publication today.

This begs the question, how much influence did Ezra Pound have in the literary world? Is what we consider important literature today valuable because Ezra Pound decided it was so? One example of Pound’s influence over writing goes back to Poetry. Pound discusses the lengths he went to encourage Harriet Monroe to print the poetry of greats such as Robert Frost and T.S. Eliot. Pound specifically discusses “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” as Monroe turned down the verse over and over again. It took Pound six months of coercion to convince Monroe to publish the work in Poetry. And today, it remains one of the most important poems in our history – evidenced by its continued explication in each and every Literature 101 course at universities around the country. If Pound did not recognize the poem’s worth, would it be lost in obscurity? Pound certainly had a great influence over which literature would later become defined as cannon.

In Pound’s essay, “Small Magazines” it becomes apparent that his involvement was huge in many of the smaller publications of the Modernist movement. He speaks as an authority on the topic and is brazen enough to criticize many of the journals while keeping an air of superiority when examining his own contributions and ideas. Pound still claims he confines “the article to statement of the positive achievement of various impractical publications.” However, Pound discusses very little of The New Age, a journal that he only refers to in passing as a “paper devoted to social and economic issues” and on a “totally different subject from that proposed to me.” These causes must have been meaningful to him as his contributions to The New Age spanned the life of the publication and were with great frequency under several pseudonyms. Perhaps his new socialist leanings also influenced his tastes in fiction and poetry. Regardless, his contributions to The New Age can’t be ignored if Pound is to be critically examined.

Ezra Pound contributed to The New Age in volumes 11 through volumes 27, writing under his given name. In volumes 22 through 28 Pound wrote under the alias William Atheling to review music in the publication and in volumes 22 through 26 he wrote under the pseudonym B.H. Dias to review art. Often, he would contribute articles and criticism under his various names within one issue. It is interesting to note that Pound did not begin using pseudonyms for his contributions to art and music until volume 22. Perhaps he did so out of a perceived necessity to fill a void in the criticism of these genres.

Pound began contributing to art criticism on November 22, 1917 in Volume 22, Issue 4 of The New Age. His first contribution as B.H. Dias is a scathing review of the gallery at Heal’s under The New Age’s Art Notes subheading. In addition to discussing the works at the gallery, Pound notes that the modern art movement on a whole has “rapidly melted into stereotypes.” This is similar to his review of literature at the time and in line with his view of mainstream magazines. It becomes apparent that Pound is in favor of new ideas and any repetition across the world of arts is unfavorable. Pound discusses the various galleries in London in which you could view many works and be left dissatisfied because they are all painfully similar. In this particular review, he goes through the paintings at Heal’s as a list using repetition in his review to mimic the repetition of the art. Pound notes, “No. 52, a sticky blurr, No. 53, a blurr (greasy), No. 54 a blurr (muddy),” etc. And while his sarcastic tone is mocking the art, he certainly elicits a chuckle when he give his most damning, yet hysterically sarcastic review of No. 57 - “57 is a sectionised blurr, a rather soggy, sectionised blurr leaning to the left and to Picasso.” Evidently, according to Pound, the art world lacked innovation and repetition ran rampant in art galleries across London. All this is not to say that Pound didn’t have a few kind words for the gallery at Heal’s. He gives a bit of positive feedback when he notes that the exhibition “is not completely displeasing.” However, the critical undertones remain in his backhanded compliment and are pervasive throughout his reviews in The New Age, easily identifying him as the author no matter which pseudonym they are written under.

In that same issue, Volume 22, Issue 4, a column written by Ezra Pound appears entitled “Studies in Contemporary Mentality.” Upon further research, it can be noted that this was a regular feature in The New Age which argues with paradigmatic views of religion, its teachings and its figure heads. Here again, Pound, writing under his given name, writes as the authority and teacher on ways in which to critically examine The Church and its offshoots. This column ties in nicely with the political leanings of The New Age, which is lauded as a guild socialist publication and guild socialists, while not particularly religious, were often found arguing the finer points of religion.

Le Mariage de Figaro, Act 2

Pound’s first contribution to the music genre in The New Age took place a bit later, in issue 6, but still within volume 22. His first review was entitled, “Le Mariage De Figaro” and opened with a tirade that seems to be the manifesto of his career. “No feeling is more typical of the conscientious Englishman, and few feelings are more annoying than the feeling that if one does not take a hand in things actively, the constituted authorities will make a mess of them.” Throughout his writings, Pound presents himself as the governing authority on all things tasteful. If the public or even the implied authorities do not follow in his perceived vision of perfection they are but dimwitted fools, or so his writings (rantings?) make it seem. Pound’s review of “Le Mariage De Figaro” asserts that the London public has no taste as the opera is closing in but a few short weeks due to a lack of interest. He argues that the commencement of World War 1 should have no bearing on the public’s interests and that the opera should remain viable as even during times of war, there are still “patrons of basket-work and dilettante pottery.” He then goes on to vilify Londoners by saying that “In any other country in Europe the intelligentsia would have gathered around and supported the Beecham production of “Figaro. Even those who had no musical sense…” Again, Pound’s pedantic writing makes it rather simple to identify him as the author.

Overwhelmingly, Pound believed that his opinions held such value that it was eminently important to spread them throughout the literary world and even into both art and music. This is evidenced in his essay entitled “Small Magazines” and throughout his tenure at The New Age, under various pseudonyms. His ideas are still today haled as genius.