Nihilism: "The desouling of the human being" Wk. 11: Surrealism (5 of 8)

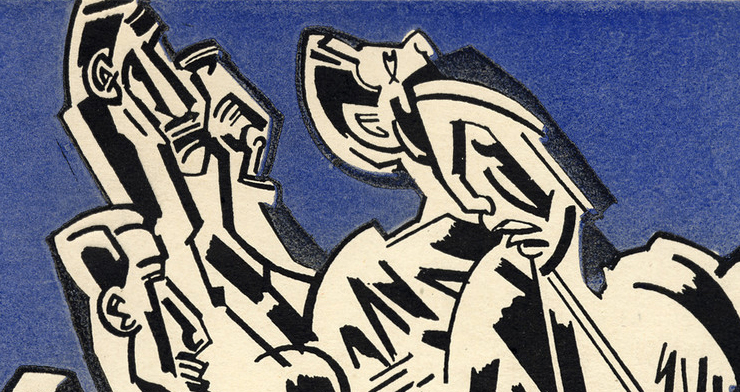

Submitted by Angela Ray on Wed, 03/23/2022 - 20:09Oswald Spengler's definition of Nihilism as "the desouling of the human being" (31, The Enemy no. 3 1929), caused me to see new and possibly abstract connections to the imagery of Surrealism. "Before reading The Enemy for this week, I had associated Surrealism only with dream-like psychoanalytic associations of the mind that are made legible through art. These are major aspects and inspiration for the Surrealism art movement, (Moffat and MacNevin, "The Origins of Surrealism)", but I was not aware that violence was an underlying component of Surrealism. From my reading of Wyndham Lewis's article "The New Romanticism'= New Nihilism'' (30), there seems to be a connection between Nihilism to the creation of Surrealist art that connects to violence that is based on the state of the world at the time of Surrealism's creation in the 1920s in Europe with its nucleus in Paris ("The Origins of Surrealism"), to the justified creation of an artistic violence. Charles Moffat and Suzanne MacNevin define Surrealism as "Psychic automatism in its pure state by which we propose to express- verbally, in writing, or in any other manner- the real process of thought" ("The Origins of Surrealism"). The violence the world was experiencing seemed to justify the creation of artistic violence that spurred the proliferation of an uber-violent spirit according to Lewis's take on Spengler. Surrealist art created the mood of the world at the time, one that was plunging towards "the strictly inhuman or rather anti-human vindictiveness that makes possible the massacres the various contemporary Revolutions, is a "nihilism": it has to credit a holocaust. But substantially it is the same as the demented doctrine of universal destruction which Dostoieffski despairingly observed, and put on record with such clairvoyance" (The Enemy (2) Paul's own account of his "new nihilism", 32). I still don't see the violence within Surrealism in its traditional forms as I did in Vorticism, Futurism, and Dadaism. But, I do notice elements of violence in the dreamscape nature of the art itself. There is something violent about the way that fish heads replace human heads and the placing of animal heads on human bodies; the contradiction of the two objects produces a disturbing incongruence of objects that is violent to me. Also, the space left in the surrealist images in relation to the objects/ people in the images seemed violent to me. The overall disorder and dis conjunction of opposing objects, and the placement of objects, created a feeling of uneasiness.