The layered experiences of the many presentations of "Prufrock"

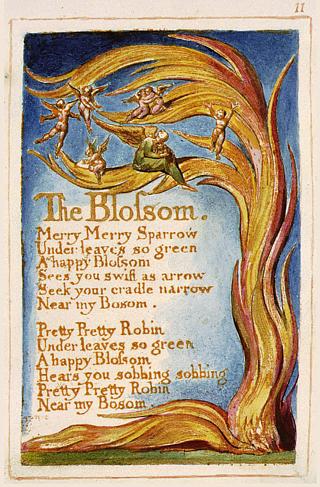

Submitted by Sydney Rubin on Wed, 09/23/2020 - 23:42After reading "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" illustrated and told through a comic format, and then the print publication of the poem in Catholic Anthology on The Modernist Journals Project https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr527353/ I began to research more recreations and presentations of this poem in the digital space. I found several animated versions of the poem set the the reading by T.S. Eliot himself, with this as one example:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xpRSmMnx1MU

I also found many celebrity readings of of the poem, but what I found particularly notable was a short artistic film that set the poem in the present day and exploring the words in the current urban city landscape.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PuvE1tfjNiU

The way that the words of the poem are spoken throughout this short movie is so quietly, some are almost a whisper. Due to the fantastic sound editing, the film manages to highlight these words and make them very audible as the main character speaks and murmurs them while moving throughout the city. This creates a deeply personal, intimate feeling that complements the candid vulnerability of the poem's voice and content in a new and fresh way.

I found that with each new version that I explored, from wide spacing that lent new meaning and a different appearance to certain lines in Catholic Antholgy that hadn't translated over to more recent collections of the poem, to the different vocal performances and readings, and what lines were included in productions and which were cut, left me with very different impressions and experiences of the same poem. Now that I have all these versions in my mind, I picture them all mentally and experience bits of them whenever I think of Prufrock.

This demonstrated something to me that I hadn't ever really thought of before; that versioning and different interpretations and experiences surrounding reading a piece of work can not only influence the experience of the original poem itself, but that these experiences layer upon one another, build upon one another, and mingle together. Though there will inevitably be parts of these interpreptations that I forget, there will be aspects of them that stick with me and inform my memories whenever I think of the poem itself or T.S. Eliot's works in general.

This layering or mixing of different presentations of a single work seems liek it would be especially prevelant in the digital age, with access to so many different publications and animations and readings of a single famous poem. If I had lived during Eliot's time, I likely would have experienced the poem through reading it an anthology or a publication, and even if each publication was formatted differently in small ways, the styles, publishing technology, and conventions for that time would have informed them and kept them fairly similar. I could have heard T.S. Eliot read the poem, or another read it aloud, but this once again would have likely been a source coming from a similar time, place, and culture. With works that have transcended cultures and time in the digital age, however, there has been time for so many myriad interpretations, readings, publications, and art forms to blossom and mingle with the poem. Nowadays, it is often not just reading a work from a single presentation many times in order to engage with it, but rather, engaging with that work in many different mediums and forms, which completely changes and informs the experience of that work.