By Emily Langhenry, Paige Krzysko, and Michelle Hwang

Throughout the beginning of the 20th century, the war that originated in Europe expanded and resulted in the First World War. The engagement in fighting and conflict that occurred around the globe affected many aspects of life for Americans and Europeans from 1914 to 1918. It not only had a political and military impact on the countries involved, but a cultural effect that specifically exposed itself through literary and commercial culture. World War I created a unique patriotic and war-focused theme that wove itself into the nuances of modernist magazines during the early 1900’s. Through advertisements in Scribner’s Magazine using a guilt-driven marketing strategy to encourage consumerism, advertisements in Poetry asking for pieces about the war, and content in Blast revealing opinions on the different countries involved, the war blatantly affected magazines using various outlets.

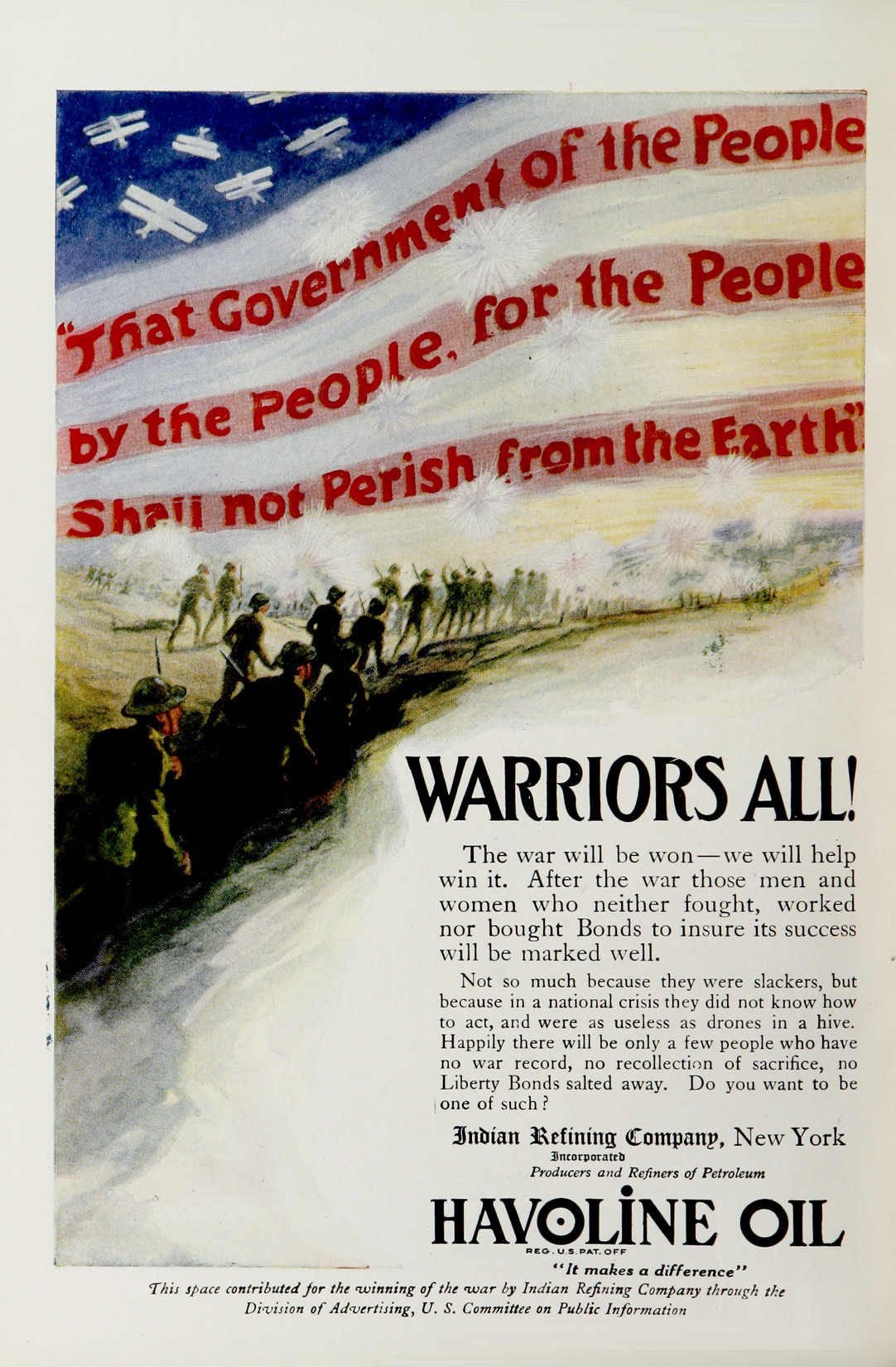

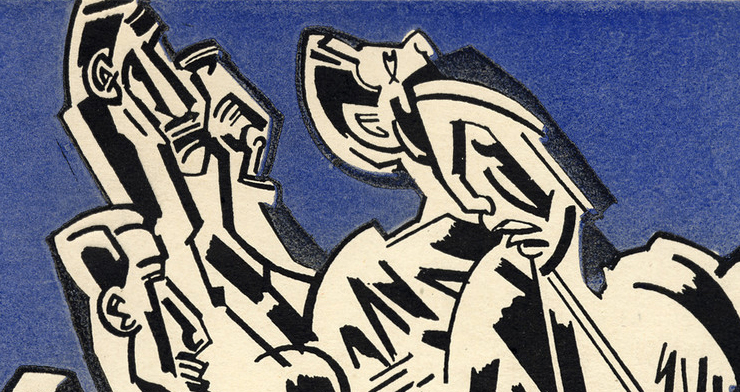

The vehicle of World War I as a marketing strategy targeting the non-military public is particularly apparent in the ads of Scribner’s Magazine. As the War progressed, so did the transition of various companies in their advertising methods. Companies went from marketing their products or their brands to marketing themselves in support of the war effort. Scribner’s magazine was an American magazine, published from New York City, which targeted a wealthier upper-class readership. A large portion of the magazine was dedicated to various advertisements, with some issues reaching nearly equal numbers of pages dedicated to content and advertisements. As such, the advertisements themselves are a reflection of societal influences. One way to see the impact World War I had on advertising is to compare the ads seen in two different issues of Scribner’s. The ads in the first issue discussed here, which was distributed in June of 1917 (only a few months after the American entrance into the War), market products for themselves. The War itself is barely discussed in ads; the topic is only breached when advertising books written on Germany and the War. Rather, readers were shown ads that marketed the product themselves. Companies did use persuasive techniques such as those that evoked nostalgic, traditionally American ideals—one example seen below is the Vest Pocket Kodak Watch advertisement (Fig. 1). However, this ad itself is also an example of how products were still marketed for their own inherent value; though the first part of the ad is devoted to evoking familiar feelings with the reader, the second explains the product itself. Another example is the Nujol Internal Cleanser ad posted in the same Scribner’s issue by the Standard Oil Company. The majority of this ad talks the actual effect and purpose of Nujol (Fig. 2). This form of direct advertising within the 1917 issue of Scribner’s separates itself from the War, seeking to persuade the purchasing public through upfront, honest advertising.

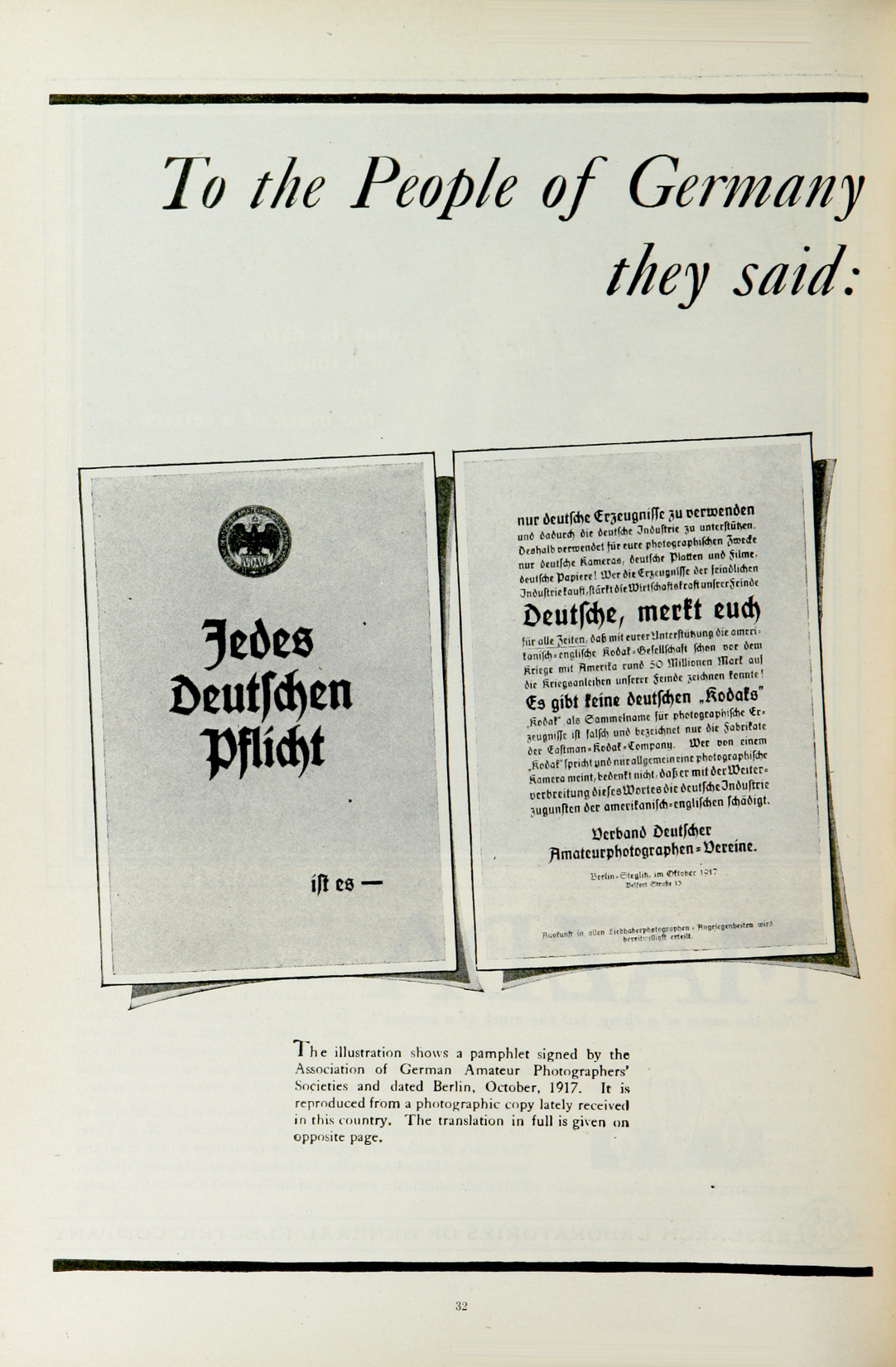

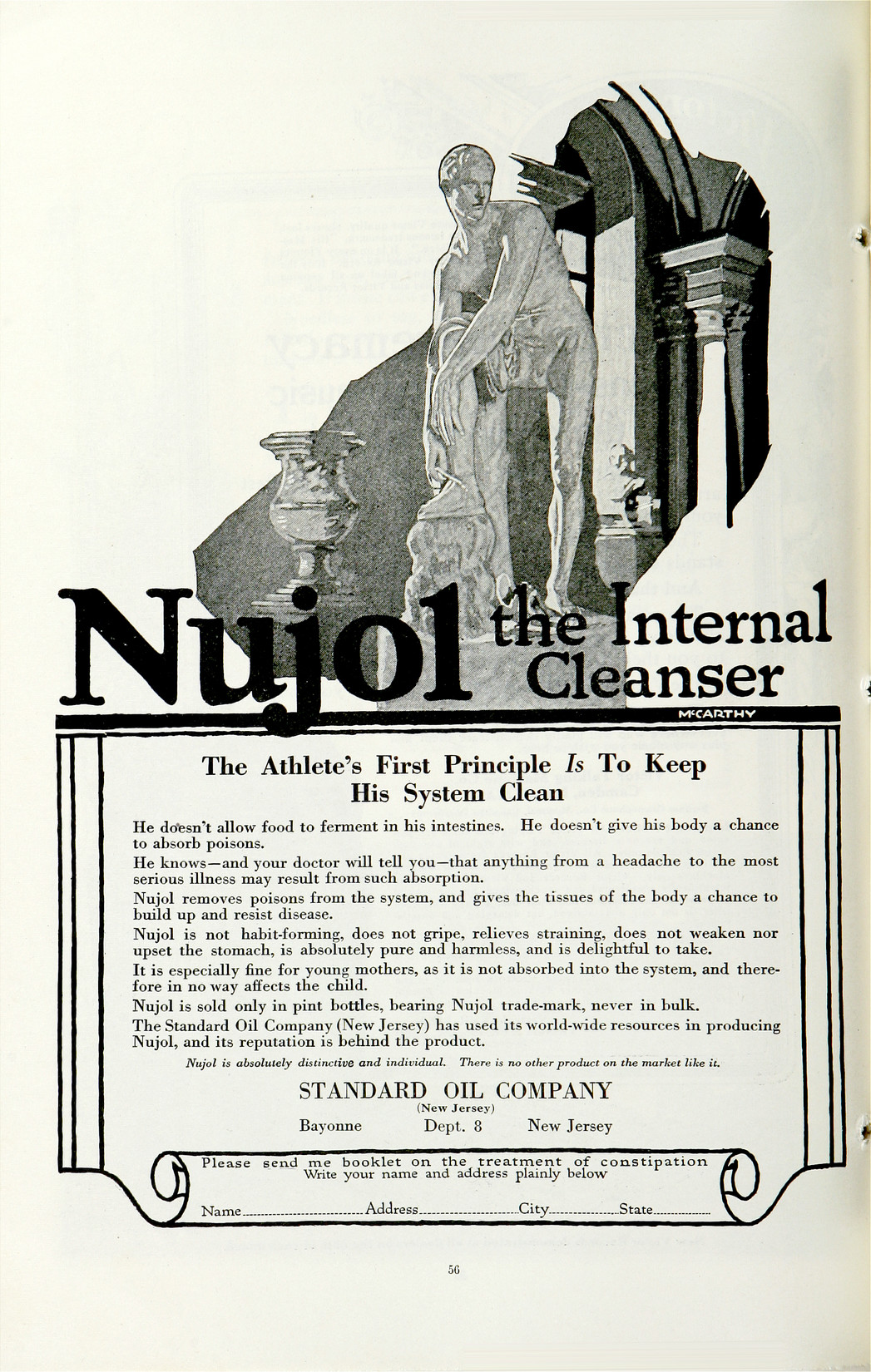

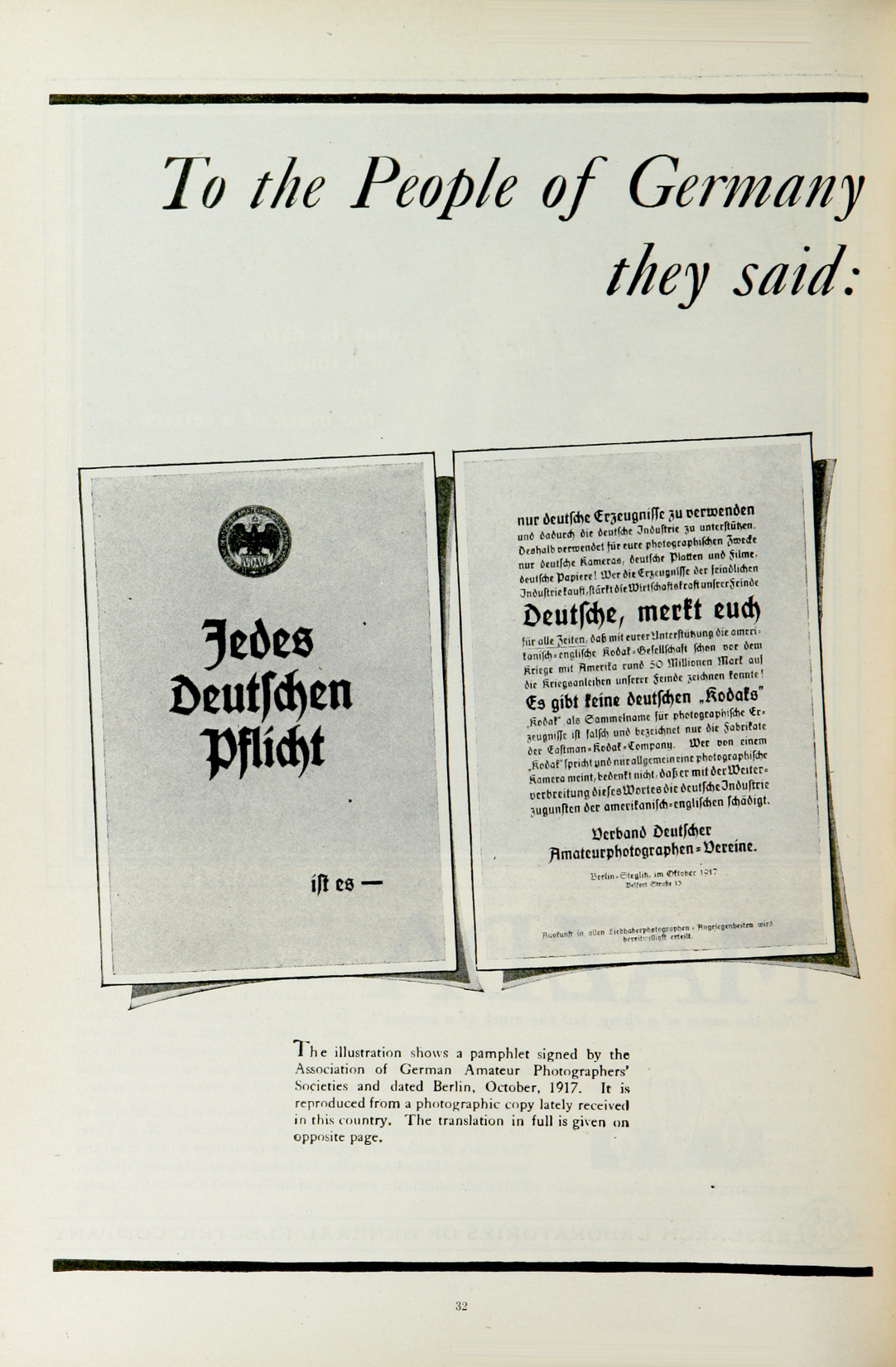

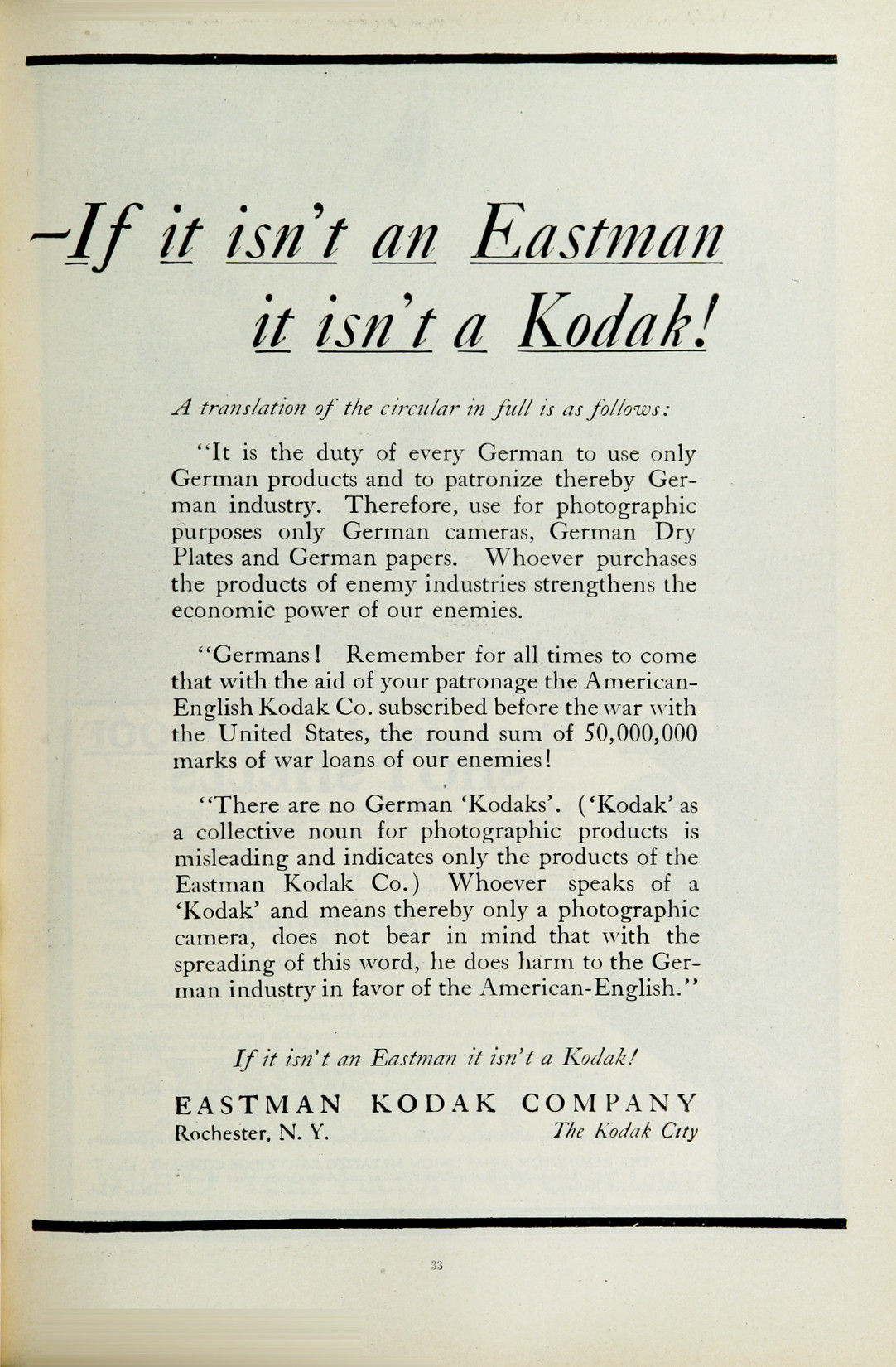

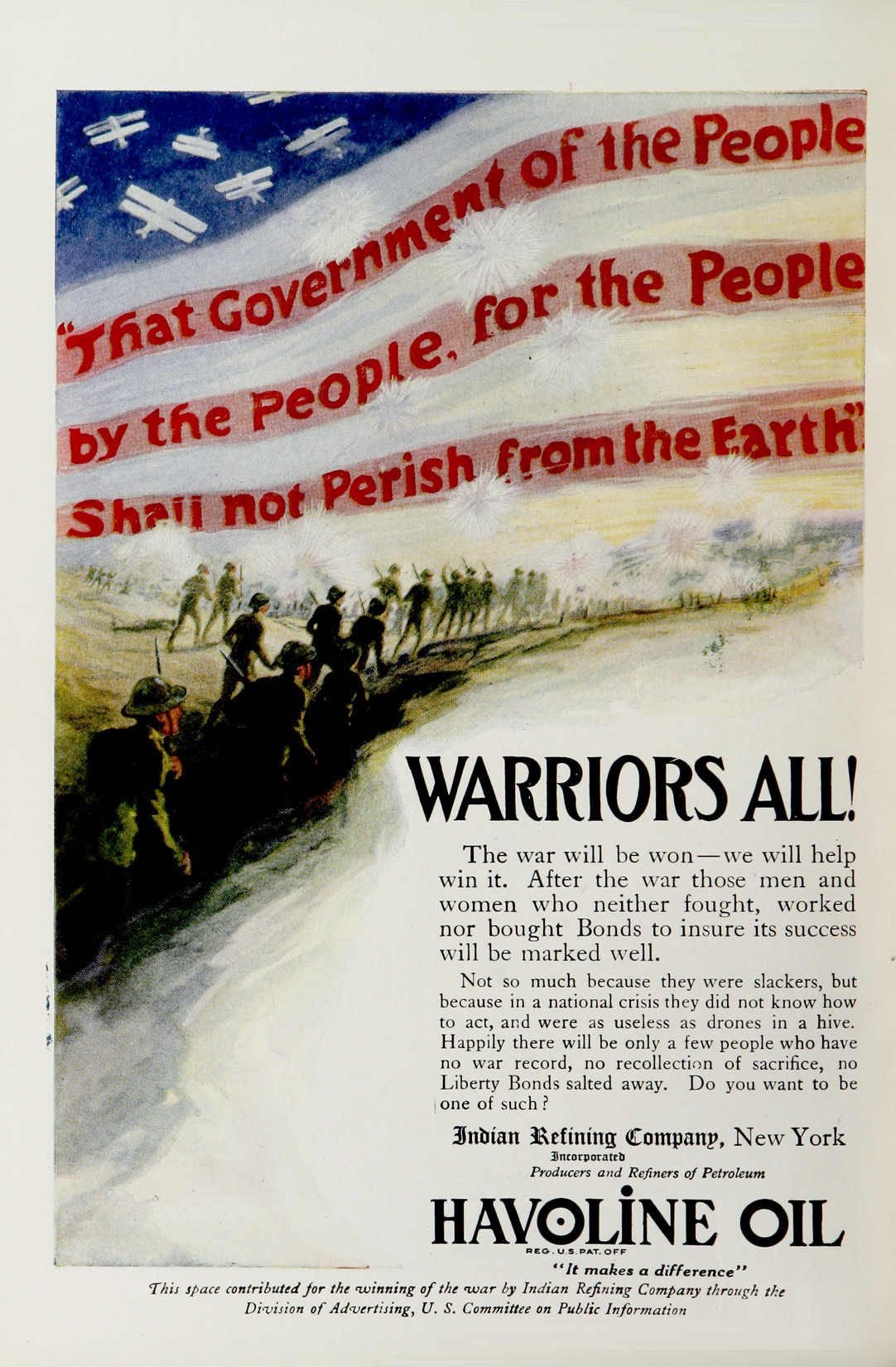

The July 1918 issue of Scribner’s published advertising that was dramatically more indicative of the War than ads only a year prior had been. July 1918 came after more than a year of American involvement in World War I, with the changes of wartime settling more deeply into everyday life. Regardless of the way the average American felt about the war, companies seized the timely opportunity to capitalize on patriotic sensibilities and feelings of guilt on the home-front. In contrast to the Kodak and Standard Oil Company ads from 1917, the ads in this later issue marketed companies’ involvement in and support of the war effort. Rather than buying a camera, consumers were pushed to purchase a slice of freedom by paying to the troops who were defending their liberties. In direct contrast to the Pocket Kodak Watch ad a year before, the Eastman Kodak Company published an advertisement for itself that markets itself simply as a company that does not associate with the German wartime enemies (Fig. 3). No details are given about products and their uses; Eastman simply wants to display its own patriotism and convince the consumer to follow in suit by buying Eastman. Oil ads, too, were altered to display greater patriotism and less product detail. Havoline Oil’s ad in the July 1918 issue of Scribner’s contains mild threats against the American citizen who does nothing (namely, no purchasing of Havoline Oil bonds) to support the war (Fig. 4). The ad says that “after the war those men and women who neither fought, worked, nor bought Bonds to insure its success will be marked well” (1918). This marked change in wartime advertising in the span of one year reveals the change World War I had on the advertising industry (and the desire of said industry to capitalize on American spirit). War itself became a means by which to guilt a wealthy, comfortable “at-home” American public into buying products that would help them repent of their lack of patriotism and fighting spirit.

Figure 1--1917 Kodak Ad

Figure 2--1917 Nujol Ad

Figure 2--1917 Nujol Ad

Figure 3--1918 Kodak

Figure 3--1918 Kodak

Figure 4--1918 Oil Ad

Figure 4--1918 Oil Ad

Aside from the representation of patriotism through advertisements encouraging involvement that appeared in magazines such as Scribner’s during the time of the war, there also existed advertisements to promote the submission of pieces that centered on the war. This was a unique type of advertising in the sense that it was self-motivated and based on magazine subject matter. These advertisements tried to control the content to focus on what was occurring around the world, and attempted to promote interest in the magazine through current events. The war was such a dominant force on culture, and that included the media. Just as anything else that is extensively covered and of popular interest, the war was covered continuously by magazines because it was what people wanted to read. In order to keep people reading, the magazine wanted to gear submissions towards popular topics. This advertising technique that was utilized at this time was smart in the sense that it not only provided publicity for the magazine itself, but also encouraged readers to voice their opinions and express feelings about the turmoil of the era. Magazines such as Poetry utilized this technique, and prior to the war there was barely any advertising at all. If issues included any, it was mostly for other magazines and literary works. Just as the war started, the magazine included an ad that asked for content that related to what was going on across the Atlantic. In the case of Poetry, not only did the war have an effect on the purpose of the ads, but the fact that it had ads in general.

In the September 1914 issue of Poetry, the year that the war began, the magazine asked readers to submit a poem about the European conflict. The best poem would receive a $100 prize, and the money acted as an incentive for submissions. The full-page ad is in the back of the issue and attempts to catch readers’ attention with “$100 FOR A WAR POEM” underlined in bold across the top (enter the link here). There is no creativity in the ad, but it jumps straight to the point to entice the audience. The ad for the contest begins by describing what the magazine was looking for and continues with the rules and where to submit entries. The description states, “Poetry A Magazine of Verse announces a prize of $100 for the best poem based on the present European situation. While all poems national and patriotic in spirit will be considered, the editors of Poetry believe that a poem in the interest of peace will express the aim of the highest civilization.” The magazine is asking for all poems that included a sense of patriotism and support of one’s country, but it also explains what the editors would like to see. The announcement almost says outright that in order to win, the piece must say why the war should end and peace be made between the countries. Poetry is an American magazine, and the mention of the highest civilization reveals itself to mean that the America is the bigger person in the situation by having the view that the conflict should end. This is a surreptitious way of encouraging criticism of what was going in Europe and displays the feeling of superiority that America promoted. It is almost asking for readers to criticize that the war is even occurring in the first place. This is ironic because of America’s entrance into the war in 1917. At this point however, the editors are asking for expressions of why it should end. By having the advertisement support content on the war and detail what opinions should be reflected in the submissions, Poetry continues the existence of war themes through commercial aspects of magazines.

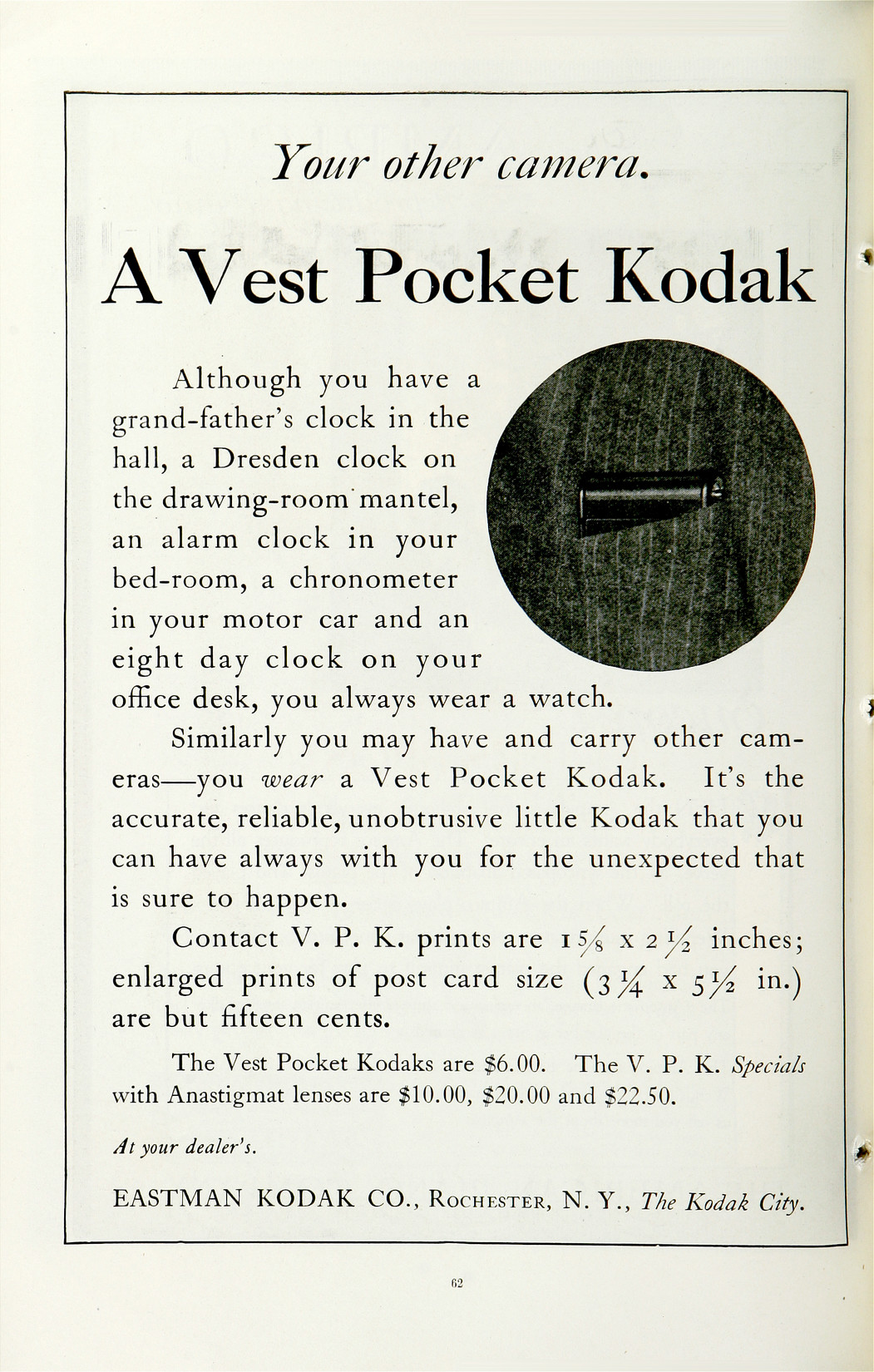

World War I did not just permeate magazine advertisements, but also spread its influence into the content of modernist magazines. One of the best-known concentrations of war-related pieces is found in the war issue of Blast. The publication of Blast, issue 2 that was published in 1915 contains heavily war inspired content. The cover itself shows humans morphed with machines falling into ranks. There is also an editorial at the beginning of the issue pertaining to the war. This editorial is the first actual content in this issue of the magazine and proves how the war had an immense impact on what was being published at the time. The beginning of the editorial discusses art as a whole and then it goes into comparing the countries of the war with traits or types of poetry. For example, the author writes, “Germany has stood for the old Poetry, for Romance, more stedfastly and profoundly than any other people in Europe,” (Blast, pg. 5). The author continues to discuss how Germany as a whole are all romantic. He writes, “The genius of the people is inherently Romantic (and also official!)” (Blast, pg. 6.) This trait is used to personify the country and create a poetic metaphor to explain the war to the readers of Blast.

This romanticism serves a purpose of describing Germany's relationship with France, then. The author writes, “The German's love for the French is notoriously “un amour malheureux,” as it is by no means reciprocated,” (Blast, pg. 6). So essentially the author is saying that the romantic nature of Germany causes them to love the French unendingly however because the French leave that love to be unrequited, Germany will stop at nothing to push its way into France. It is quite a poetic take on the war and the motivations of the various troops. It seems almost as though the author wove the situation into his usual style of writing, using this topic of romance with something such as war that typically takes on a very inhuman trait of every soldier falling into line with all the rest and simply following orders to march, shoot and kill, much like the cover of the issue. The romance gives the war a much more human face, in a way, but also manages to plant the idea of the necessity for Germany to lose in the reader's minds. The author writes, “Under these circumstances, apart from national partizanship, it appears to us humanly desirable that Germany should win no war against France or England,” (Blast, pg. 5). So essentially, the author takes a humanistic appeal to persuade his readers that Germany should lose the war. He makes a metaphor to an unrequited lover who will stop and nothing to get his way, and therefore must be stopped himself. The approach, while different from those that create the German Hun to be entirely inhumane and brute, does accomplish the same underlying impression.

World War I not only affected the politics and leadership of much of the Western world, but also permanently altered aspects of everyday life for the citizens of the countries involved. Modernist magazines could not escape the widespread influence of the war; wartime sentiments and opinions permeated throughout the covers of many publications. Even through the opinion piece in the second issue of Blast, the call for war themed poetry pieces in Poetry and in Scribner's patriotic advertisements, themes of war, the public, and art are deeply intertwined. Opinions on the war differed; some magazines built up the war effort and called for support, others denounced the seeming futility and bloodshed. Yet the range of ideas found in modernist magazines of the time only serve to display the profound impact World War I (and any war whatsoever) had on art and society.

Figure 1--1917 Kodak Ad

Figure 1--1917 Kodak Ad

Figure 2--1917 Nujol Ad

Figure 2--1917 Nujol Ad

Figure 3--1918 Kodak

Figure 3--1918 Kodak Figure 4--1918 Oil Ad

Figure 4--1918 Oil Ad